Sometime, last year, I turned my attention to coral.

It began through the meeting of three moments, one personal and two professional.

The first moment was learning that coral is used as a substitute for human bone in orthopaedic and reconstructive surgeries.

Coral is the ideal material for three main reasons. Firstly, coral’s natural porosity helps human bones regenerate through allowing new bone cells and blood vessels to grow. Secondly, coral is biocompatible to human bone, decreasing the risk of being rejected. And thirdly, because coral is biodegradable, it eliminates the need for permanent implants and possible infection.

A deep wonder ensued at this new knowledge.

The second moment was a book chapter I wrote on neon materials, called ‘Look at Me/Don’t Look at Me: A Voyage and a Journey Around High-Vis Materials; or Explorations in Fluorescent Matters’, for Tupaia, Captain Cook and the Voyage of the Endeavour: A Material History, edited by Khadija von Zinnenburg Carroll (Bloomsbury, 2023).

This chapter was a document of a dérive with my colleague Ruby Hoette, around the streets of Waterloo, spotting neon as it was appearing in the everyday, with the chapter exploring its relationship to safety and protection, which at one and the same time made neon-dressed individuals both visible and invisible.

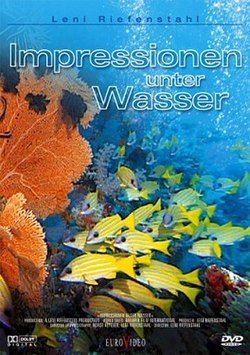

The third moment was a conference paper I heard at London Conference in Critical Thought at University of Greenwich, on a panel called Watery Speculations: Oceanic Zones, convened by Lucy A Sames. In this panel, Ifor Duncan and Sonia Levy presented a paper called ‘Masters of the Deep’, which centred on a reading of Nazi film maker Leni Riefenstahl’s late work Impressionen unter Wasser (2002).

In this presentation, Duncan and Levy reflected on “our cinematic practices and the submerged mastery, exploitation, and conflict centred around watery spaces” to challenge “how moving-image practices engage with water and political violence and how ideologies of extraction or alternatives have been performed and can be reinvented through the image-world they generate”.

It was in this presentation, I first learnt that water clarity is not indicative of healthy water, but rather that a healthy subterranean territory necessarily produces a level of murkiness.

In response to these three moments I wrote the following project description for The Coral Notes, which was both a call-to-arms and a brief for myself:

In the ocean world, clarity of vision is indicative of a lack of mineral richness; healthy waters are meant to be murky; healthy waters are meant to occlude sight.

The Coral Notes is a neon re-enchantment with the subterranean which aims to break Max Weber’s iron cage of rationality through an alchemical reimagining of it as just warp and weft, as just images and texts.

The Coral Notes takes up modernist artworks and classical philosophical texts, attending to them as material forms to be re-designed, re-presented and re-imagined. It takes those forms which appear to be seemingly clear and knowable, and muddies them into new forms.

Through this stirring up, The Coral Notes seeks re-enchant the world, to ask what, exactly, are you seeing over there?

Building on The Slime Diaries, which was centred on a relief of care that at one and the same time drove a careful retribution, a meticulous and intricate vengeance of materials, The Coral Notes steps more lightly but is no less serious in its endeavours.

With this project description in hand, I worked to gather together projects I was working on and generate new projects, with a clear trajectory to explore murkiness, and start playing with the materials that were quietly sitting in my files, folders and notes, eagerly waiting for my attention.

Since then — and at the moment — The Coral Notes comprises four works, three practice projects and one theoretical:

- The Drowned Book (CHBS#8), a set of prints made during a visit to the philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein’s Norwegian hytte in Skjolden;

- Dynamite Hidden Under The Peachy Skin, a short moving image piece inspired by the philosopher Catherine Malabou’s book The Ontology of the Accident;

- The Diagonal (Don’t Look at Me), a set of prints reworking a painting by the twentieth-century British artist Euan Uglow; and

- A Basket Theory of Practice (CHBS#6), a nascient development of Ursula Le Guin’s The Carrier Bag Theory of Fiction, which fleshes out a new critcal materialities methodology, currently taking the form of a research presentation.

There is more to come. So much more.